Heirloom Beans, Masa Dumplings, Kabocha Squash and Chicory

Norma Listman’s Sopa de Frijol con Chochoyotes y Ensalada de Chicorias

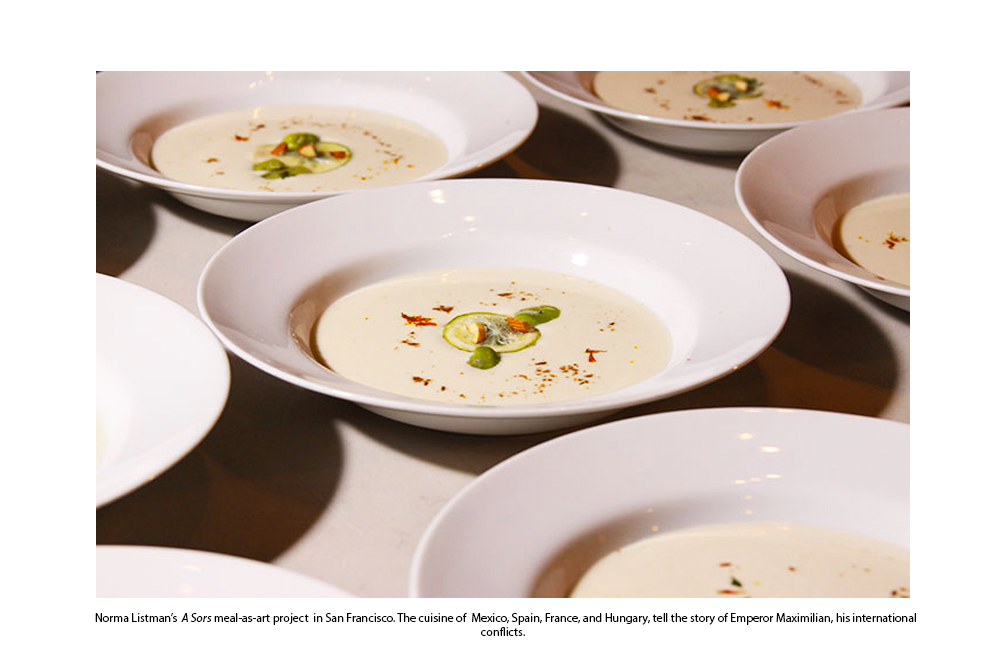

NOTES

This soup is an adaptation of a frijoles negros recipe Norma discovered in California Mission Cookery: A Vanished Cuisine, Rediscovered by Mark Preston. The chochoyotes (masa, or corn flour, dumplings) are really easy to make; it is best to make them right before serving. There are 4 different elements that compose this recipe, so you have to make sure you have them all ready when is time to plate. It is important for the soup to be warm as it will help break down some of the crunchiness of the chicories. If you cannot find Oloroso sherry, a darker, nuttier variety, any type of sherry is fine to use.

RECIPE

SERVES

5

PREP TIME

60 MINS

Bean broth

-

1cupHeirloom beans

-

3cupswater

-

4cupsbeef stock

-

1dried chile chipotle, stem and seeds removed

-

1/2medium-sizedyellow onion, chopped

-

1cupOloroso sherry

-

salt to taste

-

freshly ground black pepper to taste

Chochoyotes (Masa Dumplings)

-

1cupfreshly ground masa

-

2cupschicken, beef, or vegetable stock

-

salt to taste

Ensalada

-

1small headchicory

-

1headescarole

-

1headradicchio

-

1headfrisee

-

1/2mediumshallot, diced

-

1/4cupchampagne vinegar

-

2tbsphoney

-

1/2cupolive oil

-

salt and pepper to taste

-

1/2rindpreserved lemon rind, diced

Roasted Kabocha Squash

-

1kabocha squash

-

olive oil

-

salt and pepper

-

cumin

Norma Listman is an artist, a chef and a magnetic personality with unending passion. Arriving at her Oakland home, I was confronted with an overflowing display of seasonal vegetables, a blackberry drink made with landrace corn called champurrado, and then there was Norma, pressing tortillas by hand and popping bottles of champagne. Two of her friends, Juan Carlos Cancino of SF Greenhouses, and Saqib Keval of People’s Kitchen (two projects really worth checking out) came by to share in this bountiful Sunday meal that, as fancy as it was, was eaten on the sunny steps in front of her home.

But, this recipe was more than just a showstopper, this was one that Norma had found in her research of Mexican cuisine, and she was hell-bent on not cutting a single corner. This is her passion – mining the depths of her own culture, presenting it in all its delicious complexity. This dish is a treasure among everything she has discovered in her archaeology of culinary history.

Norma Listman in Her Own Words

Julia Sherman: Tell me how you started cooking? Did you have formal training?

Norma Listman: I have been cooking ever since I can remember. I started very informally and empirically. I have always pursued eating well and cooking for others.

I do not have any formal training. Eight years ago I decided to change my career and pursue a career in food, but I was afraid to dive into professional kitchens because I lacked formal training. One day I decided not to let that fear of the unknown win and I knocked on Chef Anthony Strong’s–from the Delfina Group– door. He gave me my first kitchen job and he has been a great mentor since.

JS: Do you consider yourself a chef, an artist, or both?

NM: Both.

JS: Tell me about growing up in the countryside outside of Mexico City and how that influenced you and your work with food?

NM: I grew up in Texcoco, a town on the outskirts of Mexico City. It used to be one of the shoreline towns when the ancient city of Tenochtitlan and Lake Texcoco existed.

I grew up surrounded by family and food. My great-uncles had pigs and chickens and little vegetable gardens. I rode horses in the countryside. Every other day my grandfather and I bought raw milk from the farm of a famous bullfighter.

The same uncles had an outdoor wood oven that they used to make “pulque pan de muerto” during the Dia de Muertos festivities. My upbringing was woven with food and tradition, and I love the countryside of Mexico, as much as I like Mexico City.

JS: From there, how did you end up in Mexico City? What was it like back then?

NM: In contrast to my country childhood, I attended a private high school in Mexico City. There, I became interested in art and hung out with the creative people in the city. That was in the 90s, when the freedom in Mexico City was unparalleled. I went to fancy restaurants, art openings, punk shows, ate at questionable late-night food stands and danced with ficheras.

At 19 I got my first apartment as exchange for work at an art gallery. I was young, very young, and sometimes we had no money to pay the bills. Some friends and I started throwing parties to fundraise and oftentimes I could only pay by cooking for them the following day. These parties, lifestyle and a social dynamic opposed the rigid rules dictated by the art world and society in general, and it only fueled my desire to feed people.

JS: And what is so special about the food in Mexico City?

NM: The valley of Mexico has an incredible wealth when it comes to culinary tradition; food there is diverse, ancient and contemporary. That history inspires the narrative of my work, but it is that freedom of the urban context that inspires me to create, whether that takes the form of an underground restaurant in West Oakland or a surrealist menu in honor of Remedios Varo, Mexico City–that city is the lifeblood of my work.

JS: Your food is very focused on history, what is the attraction there? How do you communicate through food?

NM: I love this question! I understand the world through the food we eat. If we pay close attention to the evolution of food, we can understand humankind. The geographical origin and movement of ingredients and technique fascinate me.

There was a point in my life when I wanted to be an art restorer. But when I find and adapt old recipes, I feel I am doing enacting a form of “restoration.” An experience is revived through the recollection and recreation of an old recipe, and we get the opportunity to experience the past. This is sensorial time travel.

This is also a political act, to trace ingredients and technique. I decide through my cooking on what side of history I stand.

JS: Tell me about some of the research projects you have done.

NM: I became really interested in the history of Mexican food in California, which led to a collaboration with Julio Morales. The project explored the transfer of Alta California from Mexico to the United States in 1846. The project studied and interpreted Mexican General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo’s last 8 hours in power. The project had many layers, food being the spinal cord, the and we shot in Sonoma, at Vallejo’s house. As I was doing my research of the Californio’s dressing customs, I started learning about their food traditions, and from there I was hooked.

I had already been doing research about food in Mexico, but this project opened my eyes to a whole new world of Mexican food, the food of the Californios.