Cucumber, Lychee and Mango with Fried Shallots and Spicy Lime Dressing

Amy Thielen’s Hmong-style Fruit and Cucumber Salad with Fried Shallots

POSTED UNDER

- North Carolina,

- Travel

NOTES

This is the perfect summer salad – chilled, a bit spicy and a bit sweet. The use of cilantro stems in the dressing blew my mind (this is what happens when a chef improvises).

RECIPE

DIFFICULTY

MODERATE

SERVES

6

PREP TIME

10 MINS

Salad

-

5kirby cucumbers, peeled and cut into chunks

-

2mangoes, peeled and cut into chunks

-

12lychees, peeled and cut into chunks (fresh or canned)

-

4sprigsmint, torn

-

2sprigsrau ram or 4 sprigs Thai basil, torn

-

5medium shallots, sliced crosswise

-

1/4cupcanola or peanut oil

-

salt for shallots, to taste

Dressing

-

2thai chiles, minced

-

2kaffir lime leaves, minced (substitute 3 strips lime zest)

-

2stalkslemongrass

-

3TBScilantro, minced

-

1/4TSPsalt

-

3TBSsugar

-

1TBSfish sauce

-

7TBSlime juice

-

1TBSwater

POSTED UNDER

- North Carolina,

- Travel

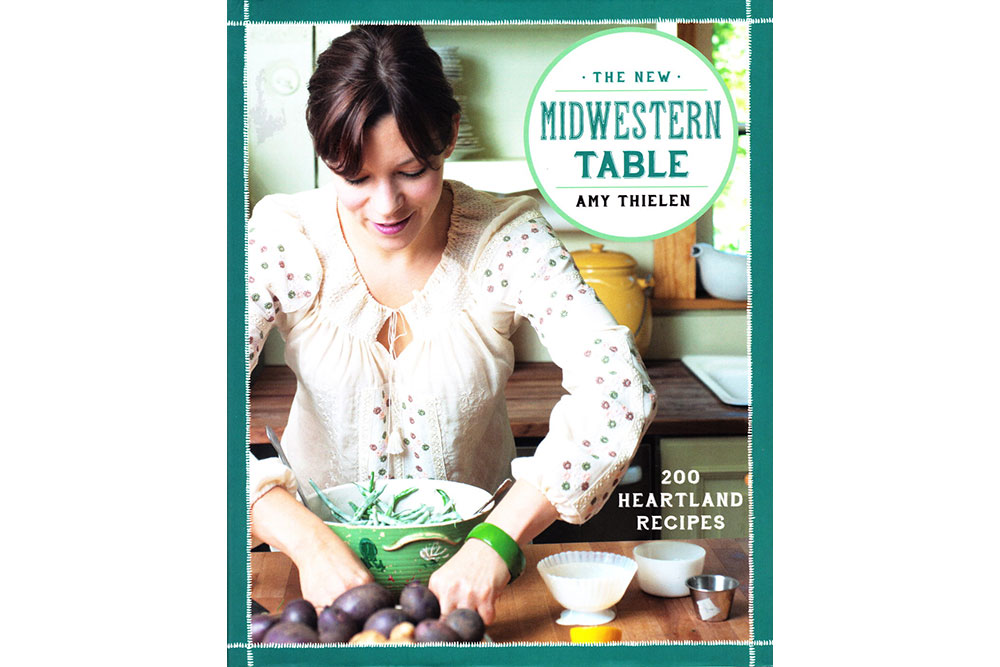

When I put my salad feelers out in anticipation of a trip to Minneapolis/St. Paul, there was a resounding endorsement all around — Amy Rose Thielen! Amy, born and bred in Minnesota, has embodied the diverse spirit of the Midwest through her food and writing. She is the author of the award winning The New Midwestern Table, host of her own TV show and the soon to be author of a memoir.

After years in the kitchen with Jean Georges and David Bouley, Amy her and her husband, sculptor Aaron Spangler, returned to their home state, to build a life on his family’s property (when you have a couple as resourceful as their two, anything is possible, even living without electricity for some time). Now, having built a beautiful property for themselves and their son, they host their artist friends from NY, MN and beyond, showing them how real homesteading is done – hunting, harvesting wild rice in canoes, and growing and preserving your own food. Not because it’s trendy, but because they have to.

Amy and I met in St. Paul, MN, where she was visiting for a few days. Without a kitchen to prepare her salad, Amy proposed a trip to the Hmong market by her mother’s house, where Laotian immigrants sell sky-high piles of herbs, twigs and what look like rocks for medicinal tea, textiles, dvd’s and most importantly, fruits and vegetables. Amy managed to show me a completely unexpected side of town, one where the fruits are exotic and the population incredibly diverse.

Amy Thielen in Her Own Words

Julia Sherman: You have worked in some of the most high octane New York kitchens. Now you live in a pretty remote part of Minnesota, where you garden, hunt, write and shoot, write cookbooks and work on your own TV show. Tell me how you ended up living where you do, and what that transition was like?

Amy Thielen: Julia, I don’t really hunt myself, although I cook the spoils.

After we had Hank, we started spending summers back here, in the cabin that Aaron had built in his 20s. (We’d lived out here in the summers, in a much more rustic way, without power, before we moved to New York in 1999.) All of our friends in New York said, “You’re never coming back.” And eventually, they were right. I think that after we had Hank both Aaron and I felt the need to focus a lot of time on both our work and our home life. I wanted to keep working on what I called my Midwestern food project and write a cookbook, and Aaron wanted to keep making a lot of art. So moving back to the house outside our hometown of Park Rapids made a lot of sense. We travel to New York a handful of times a year for work, but we live in the woods house full-time. Aaron has a bigger studio here, Hank has grandparents, and I have the garden to cook from, which is so inspiring to me that it now feels totally essential to what I do. I’ve found that my best ideas for recipes and combinations come when I’m faced with a surplus.

No place is perfect, though, and for better or for worse, northern Minnesota lacks the distractions of New York. Especially in the winter, when all the visitors and summer people leave and the garden freezes and the snow drifts over the road. Then the only thing to do is work.

But even though New York and Park Rapids are about as opposite as two places could be, something about them feels similar. They’re both dramatic, in different ways. New York was high drama for obvious reasons—the constant thrill and stress of my being a cook and Aaron in the art world—but the severe cold and our remoteness both have their own intensities. And being back in my hometown, which I never thought would happen, is weird, too. I have a complicated relationship with the place, very emotional. Sometimes I hate it, and then at other times my fondness for it is overwhelming. I guess that alone is puzzling enough to keep me here.

JS: How did you come to host your own TV show? There must be so much content that doesn’t make it into the final edit. What are some of the scenes or stories that you would still like to share, but that ended up on the cutting floor?

AT: Lucky me, I kind of fell into hosting the show. My cookbook, The New Midwestern Table, was still being edited at Clarkson Potter when I got the call from my agent telling me that Peter Gethers at Random House Studios was interested in producing a TV show based on my book, and he’d already talked to Lidia and Tanya Bastianich about co-producing. I was pretty awestruck, but totally game. I mean, Lidia’s show has been one of my PBS indulgences for years, and I knew that Peter would only want to make smart, interesting, fun TV. We were all thrilled to sell the show to Food Network.

My favorite outtake from the show actually made it into the show. In “Granny-Style Chicken,” the main event was a stuffed, roasted chicken from a local farmer, who sent it over with the feet still attached. I thought it might be cool to show how to whack off the feet, so I got out my cleaver. This turned out to be harder to do gracefully than I first thought. On the first whack one foot went flying across the kitchen; I broke my cool and laughed so hard you could see down my throat. Second foot, same story in the other direction. I was sure that this bit would be cut, but part of it made it in.

During the second season, the director and I also had a dumb recurring joke that used to crack us up. In a cooking show there are so many moments when the host says, “Marinate this in the refrigerator for at least thirty minutes.” And she’d coach me to end it with “and as long as nine months,” or some other super-long time. It’s really not that funny, but when you’re tired and it’s the end of the day, it just slayed us.

JS: Your husband is a sculptor. You are both makers. How do your individual practices intersect, if at all?

AT: I think we’re both really interested in rural life and how people make their own culture. Art, music, food, books, beautiful things…these things are just as possible in the middle of the woods as they are in the middle of Manhattan—the only difference is that sometimes in the country you have to be the maker.

I also think that creatively we’re both very process-driven. We both make discoveries by working through and transforming the material. In my case, that means I cook a lot, and unless I’m testing recipes, I cook very improvisationally—like I did today! If you come to dinner at my house you’ll never eat the same thing twice, though you might see different renditions of a dish—something I’m working out. In Aaron’s case it means that his images slowly emerge through a gradual process of reduction, of carving. He doesn’t begin a carving with a detailed sketch; he finds his subjects.

Another thing: in a lot of ways our work is indivisible from our home life. Aaron spends a lot of time making sculptures in his studio, but he also spends a lot of time making trails and new spaces on the land. Every year when I hear the chain saw going down by the creek I know it must be spring, because Aaron’s cutting down trees. (We have a lot of trees, and we use them, so no one should feel bad.) It’s his way of carving out the hill and revealing its natural shape. It’s sculptural, really. In the same way, I often find myself canning and otherwise preserving the harvest, and forgetting to take pictures and blog about it. Sometimes I’m so busy with my life, I don’t have time to document it. Where does work start and real life begin? Hard to say, the line is very blurry.

And weirdly enough, our practices also intersect literally in sharp steel. He works in wood, so has a wheel to keep his chisels sharp. And I have a small collection of Japanese knives that I use a whetstone to sharpen. (Truth be told, though, my knives were a hell of a lot sharper when I was working professionally than they are now. My blades have gone civilian.)

JS: Tell me of your dreams to create a residency on your property. What would that look like?

AT: I’m working on a plan to build a cooking school on our front 80-acre field, with an art exhibition space that doubles as an event hall, and the residency would spring out of that. I really want to make myself a commercial kitchen, so that I can cook again for greater numbers, and teach more people. We’ve long thought about getting a residency going here to provide a place for artists or writers to get away from the city and have the time to focus on what they need to make. We’re inspired here, so we hope that other people feel the same.

JS: I learned so many interesting things just spending the day with you, but the most captivating was the story about the gorgeous wild rice you gifted me. I had no clue that in all my life, I have probably never actually had truly wild rice. Can you tell me how you harvest this stuff?

AT: Let me know what you think of that bag of rice I gave you! I’m a real advocate for real wild rice, which is always light brown, never black. (Cheat sheet: real wild rice grows naturally in lakes and rivers, and is hand-harvested and parched over a wood fire. The black stuff is grown in a paddy, harvested by combine, and steam-parched. Botanically, they’re not even the same.) Wild rice has grown in Indian Creek, the waterway that encircles my house, for hundreds of years. It grows wild in creeks that have beavers monitoring the water level, and there have been beaver dams on Indian Creek for as long as anyone here can remember. Aaron harvests the rice via canoe and then we take it to neighbors on White Earth reservation for wood-fire parching. Real wild rice is tender and light, smoky, and actually delicate. I like it any time, but especially for breakfast with butter, toasted nuts and maple syrup.

JS: As a former English major turned chef is writing cookbooks the idea use of your skills?

AT: It’s the perfect synthesis of my skills, though I didn’t realize that until years after I started cooking. Back in college, I thought I’d become a writer. But I always turned to cooking to procrastinate and put off doing my work. You know: 24-page term paper due? Let’s throw a Thai dinner party for twelve! Cooking has always been the thing that I can make myself do. Eventually I procrastinated writing so well and so often that I didn’t do it all, and I decided to become a chef. Years later, when I was wading deep through my first big writing deadline for my cookbook, I thought: wait a second! I use cooking to procrastinate from writing, now what do I do? It was both a total dream and a nightmare, because the two parts of myself had smashed together and I had nowhere to run.

JS: How does writing a memoir differ from writing a cookbook with a very personal cookbook?

AT: It’s very different. My cookbook was a love letter to this region and to all the beautiful meals that people have made in it over the years. The headnotes are stories, vignettes. But part of the success of that book is also due to the images by Jennifer May, and the illustrations by my neighbor Amber Fletschock. They both totally understood my vibe and captured it—the repressed nostalgia, the dark corners, the wry humor. They really brought it.

My upcoming book is less nostalgic and more self-analytical. I think it’s also funnier. The story begins in my childhood in this town at the top of the Mississippi river, home to one of the largest french fry factories in the country—not exactly a foodie wonderland, is it? We’re talking about northern Minnesota in the 1980s. I grew up pouring coffee at fundraising “scoop dinners” where balls of hamburger hotdish fell out of ice cream scoops onto your plate. My path to New York City and to seven years of cooking on the line in top fine dining kitchens, and then our migration back to the cabin in the woods, was not an obvious one—but I think it’s a pretty great story, and I hope I’m doing it justice. Aaron and I have never made a safe decision in our lives, which in retrospect makes for a youth full of good material.

JS: What do you want us coast-clinging folks to take away from your cooking and your focus on Midwestern food culture?

AT: I think any home is worth investigating, and regionalism is worth protecting. That said, it’s just as important to absorb all the new local cooking influences as it is to catalog the old. Take, for example, our day here in St. Paul. We hit the Hmong Marketplace is in Frogtown, a St. Paul neighborhood that once was home to a bunch of my French-Canadian immigrant relatives. My great-grandma had a pop-up restaurant not far from here. I think it’s so incredibly cool that I can return to my family’s neighborhood and find this place—which is like a Hmong village transported—and then go to Como Park, where I grew up barbecuing with relatives, and do some grilling in the style of this neighborhood’s new inhabitants. I love the Hmong Marketplace, and I love how they’ve made a home here. Frogtown’s is a crazy-delicious portal for newcomers.

JS: What’s the deal with Walleye?

AT: Walleye is good, but in truth it’s not my favorite. It’s a beautiful fish, fillets like a dream, and it freezes well—which is why it’s so popular around the country. But I think it lacks the flavor and juiciness of the harder-to-fillet Northern Pike, or even pan fish like Bluegills and Perch.